The Inside Story

The Inside Story

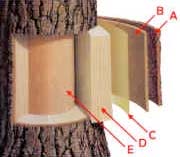

- The outer bark is the tree’s protection from the outside world. Continually renewed from within, it helps keep out moisture in the rain, and prevents the tree from losing moisture when the air is dry. It insulates against cold and heat and wards off insect enemies.

- The inner bark, or “phloem”, is pipeline through which food is passed to the rest of the tree. It lives for only a short time, then dies and turns to cork to become part of the protective outer bark.

- The cambium cell layer is the growing part of the trunk. It annually produces new bark and new wood in response to hormones that pass down through the phloem with food from the leaves. These hormones, called “auxins”, stimulate growth in cells. Auxins are produced by leaf buds at the ends of branches as soon as they start growing in spring.

- Sapwood is the tree’s pipeline for water moving up to the leaves. Sapwood is new wood. As newer rings of sapwood are laid down, inner cells lose their vitality and turn to heartwood.

- Heartwood is the central, supporting pillar of the tree. Although dead, it will not decay or lose strength while the outer layers are intact. A composite of hollow, needlelike cellulose fibers bound together by a chemical glue called lignin, it is in many ways as strong as steel. A piece 12″ long and 1″ by 2″ in cross section set vertically can support a weight of twenty tons!

Leaves Make Food for the Tree

And this tells us much about their shapes. For example, the narrow needles of a Douglas fir can expose as much as three acres of chlorophyll surface to the sun.

The lobes, leaflets and jagged edges of many broad leaves have their uses, too. They help evaporate the water used in food-building, reduce wind resistance—even provide “drip tips” to shed rain that, left standing, could decay the leaf.